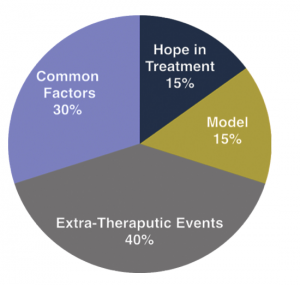

At Ellenhorn, we place collaboration in therapeutic relationships front and center. In such a relationship, therapist and client work to achieve goals the client identifies as important, and that both agree they have the power to reach. This is very different from a relationship in which the clinician, as an expert, figures out what is wrong with the client and prescribes a particular treatment protocol to fix it.

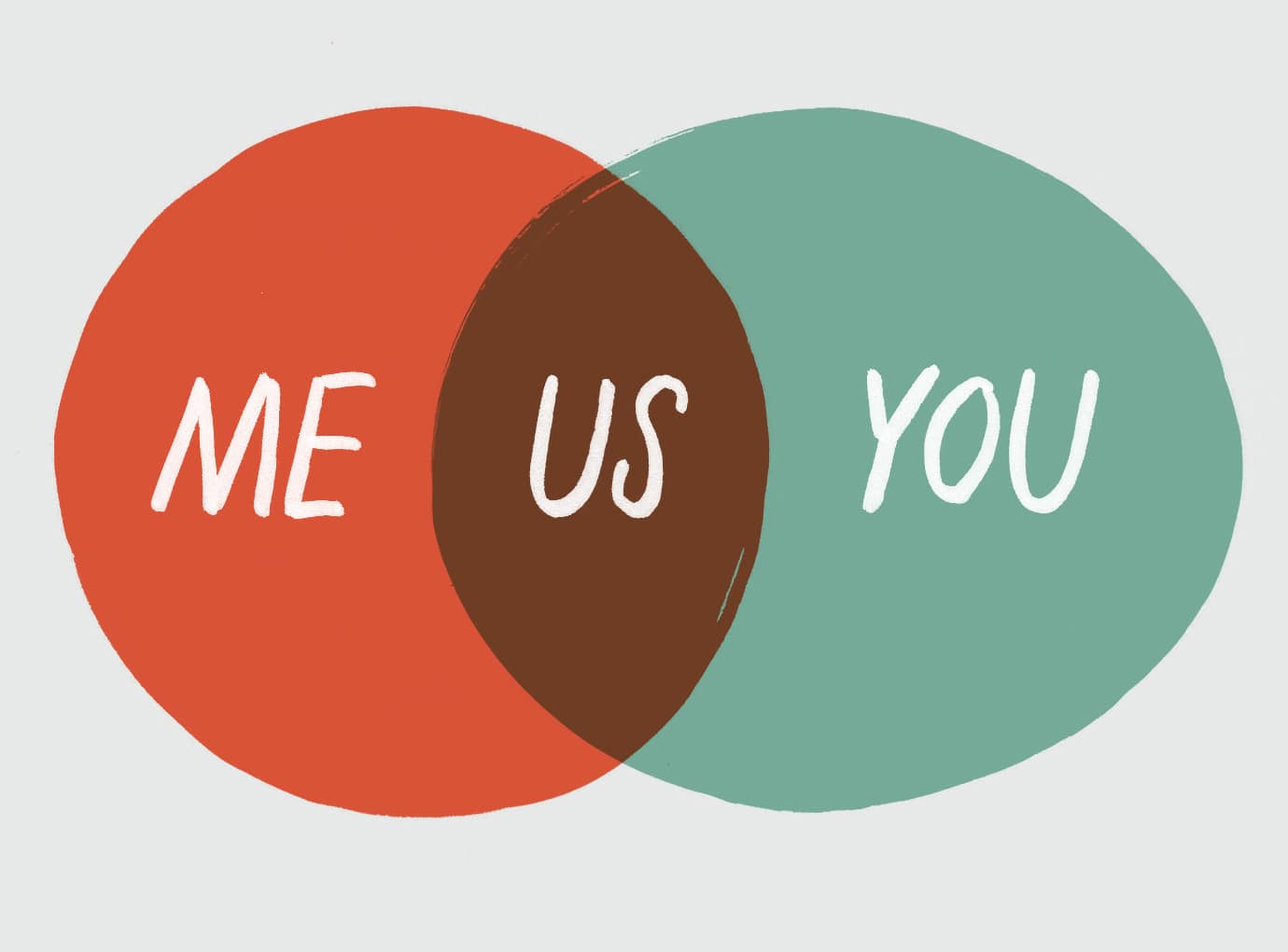

You can’t really talk about a collaborative therapeutic relationship without talking about a “treatment contract” that provides a sense of where client and clinician are going. With that in mind, we call our plan the “Roadmap to Recovery,” and we’ve built this therapeutic contract to be collaborative. The graphic below presents a picture of how we think about the Roadmap to Recovery.

“If everything goes well here, what will your life look like six months from now?” That’s the question we typically ask while building our Roadmap. The answers form the “dream” at the top of the graphic. Once we understand their dream, we work with clients to mobilize their strengths, and to remove as many barriers as we can, in order to achieve it.

That simple idea makes our Roadmap different from a typical treatment plan in which symptom reduction or behavioral change is the goal. We work on symptoms and behavior with our clients, but only in pursuit of larger life-goals. Thus, the typical fodder for clinical interventions is not our central target. The dream is our focus for our clients, the destination we share. Most often, psychiatric issues emerge as barriers to reaching this destination, and together we work to remove these.

“Collaborative therapeutic relationship”: the words have a nice ring to them. And they do point to humane and decent sentiments. But collaboration is more than a nice value. The collaborative relationship is scientifically proven to be the most effective kind of relationship in facilitating change.

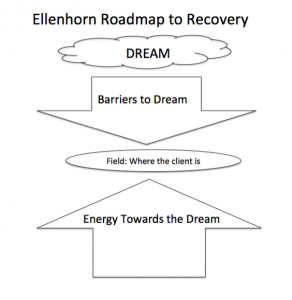

This pie chart captures a surprising fact: A hefty 30 percent of client change results from “common factors” in the relationship between client and therapist, that is, behaviors and attitudes exhibited by therapists, independent of the therapeutic approach they use, that promote change in clients. As shown here, common factors are doubly powerful as change-drivers compared to specific therapy models.

This pie chart captures a surprising fact: A hefty 30 percent of client change results from “common factors” in the relationship between client and therapist, that is, behaviors and attitudes exhibited by therapists, independent of the therapeutic approach they use, that promote change in clients. As shown here, common factors are doubly powerful as change-drivers compared to specific therapy models.

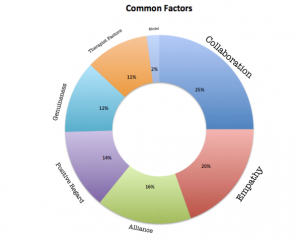

Researchers have gone deeper into the question of what promotes change, examining which common factors are most important. As the next chart shows, a collaborative approach is the winner (surrounded by its sister, alliance, and its cousins of empathy, genuineness and positive regard).

When we at ellenhorn are able to form a collaborative relationship with our clients, discussions with them that otherwise would place significant power in the hands of clinicians, take on an egalitarian hue. No longer are we assuming that our formulations, diagnoses and prescriptions are the unquestionable guides for treatment. Instead, we engage in a conversation with our clients in which we look at how psychiatric experiences, along with other factors that play a role in all our lives, may hamper our work to reach their dream. This approach levels the playing field, giving the client significant voice. It doesn’t silent our opinions; rather, it gives us the ability to say what we think is happening without our opinion carrying more weight than theirs.

“At ellenhorn, I’m allowed to have my own experience,” says one client. “No one is trying to convince me, or pathologize my disagreements with them, saying ‘You’re in denial’ or ‘You won’t get well if you don’t see you are sick.’”

There’s a lot of room on the team for different voices,” she continues. “It’s a polyphony, rather than a unified front. And I have a central voice in this polyphony. That’s a big relief for me, since I’m no longer judged as just a patient with no agency or input. I can voice my doubts and express sadness, and have appropriate feelings about what’s happened, without feeling like someone is diagnosing me.

When this client gives an example of the times when she most felt the effects of our collaborative relationship, her answer points to an important and unique way we work:

“I’ve never had a group of friends who all saw me at the same time in my own environment and saw what was going on, and then approached me with that shared knowledge. At ellenhorn, for the first time I have multiple people seeing and communicating with each other about how I am doing outside of therapy. That’s the most important factor. It’s really important that there are all these multiple views that can be checked with each other, and are windows into my world.”

This client felt the strength of our collaboration outside our offices, in her own home. Her response captures another important factor in change: a person’s life outside therapy, or “extra-therapeutic events.” As the chart above indicates, they embody 40 percent of the factors that either produce or block change.

As the most robust community integration program in the U.S., we focus on these outside-the-office issues. We do so collaboratively, combining the two most prominent supporters of change into one. That means we put a lot of energy into issues other than a client’s purely psychiatric symptoms, working alongside our clients in the community to both deploy their strengths to reach their dreams, and remove barriers to these dreams. “I was afraid of the visibility an outreach team would impose,” our client says. “But it turns out that it’s this very visibility that has made my time with ellenhorn so productive. Allowing myself to be seen and known and even seen in different psychological states — these things have to be seen literally by someone. And having them seen in my own environment, without people judging me, makes feel like I don’t need to hide anymore.”

Community integration programs, especially ones as comprehensive as ours, are often called “hospitals (or residential programs) without walls.” The concept of “without walls” sounds innovative, accessible, hospitable. But walls don’t only keep people in; they also keep people out. When mental health workers serve people in the community, they’re given access to their clients beyond the usual barriers of privacy the rest of us enjoy. When professionals walk through the doors of their clients’ homes to treat them, they wield significant power based on their ability to survey the most private parts of people’s lives. But when we focus on having a collaborative relationship with our clients, that potentially coercive and monitoring spirit gets turned on its head. Instead of entering a home from a position of power, we enter it with our eyes on where the client wants to go, and how we can help them get there. Our client beautifully captures this union of collaboration and treatment in the community:

“Even though my entire history says I would find it threatening, I can now say that people coming into my apartment doesn’t feel threatening at all: it’s actually felt very freeing to have somebody come over and just check in and see what I’m doing. That would never happen in any other context.”